DEEPER LOOKS

The Future of International Norms:

US-Backed International Norms Increasingly Contested

This paper was produced by the National Intelligence Council’s Strategic Futures Group in consultation with outside experts and Intelligence Community analysts to help inform the integrated Global Trends product, which published in March 2021. However, the analysis does not reflect official US Government policy, the breadth of intelligence sources, or the full range of perspectives within the US Intelligence Community.

Diverse global actors with divergent interests and goals are increasingly competing to promote and shape international norms on a range of issues, creating greater challenges to the US-led international order than at any time since the end of the Cold War. Some democracies are retreating from their longstanding role as norms leaders and protectors as populist influence grows. At the same time, authoritarian powers led by China and Russia are reinterpreting sovereignty norms, offering alternatives to what they view as US-centric norms, such as individual human rights, and using norms and standards to promote their influence. Nonstate actors and smaller states are often key players who try to overcome normative impasses and, in some cases, step in to fill perceived gaps. During the next decade, this increased competition will limit the effectiveness of international efforts to address global challenges and increase the risk of armed interstate conflict, although major powers are still likely to uphold norms in mutually beneficial areas.

Scope Note: This paper focuses on selected international norms supported by the United States that we assess to be most under stress, particularly in the human rights and security areas. It draws on norms in other areas including sovereignty, environment, and economics. The focus is not on the future of global governance or international institutions, and it avoids commenting on broad principles, social and domestic norms or technical standards. Principles articulate group goals and visions but do not assign responsibility for achieving them. Technical standards are norms that articulate consensus regarding the specifications for a particular technology, signal, or system.

DEFINITIONS

This paper examines the future of international norms during the next decade using the following definitions:

- Norms: Shared expectations about what constitutes appropriate behavior held by a community of actors. Norms can form at the international, regional, state, or sub-state level and attempt to guide desirable behavior.

- International norms: Widely shared expectations about what constitutes appropriate behavior among governments and certain non-state actors at the international level. Non-binding frameworks, such as voluntary codes of conduct or conventions, sometimes set the scene for more formal, binding agreements.

- International legal norms: Generally referred to as international law, these norms are binding on actors and typically formalized in written agreements, particularly treaties.

- Norm entrepreneurs: Actors who leverage the reputational sensitivity among states and other entities to develop and lobby for norms. Many norm entrepreneurs seek to encode norms in legal instruments to improve and broaden compliance.

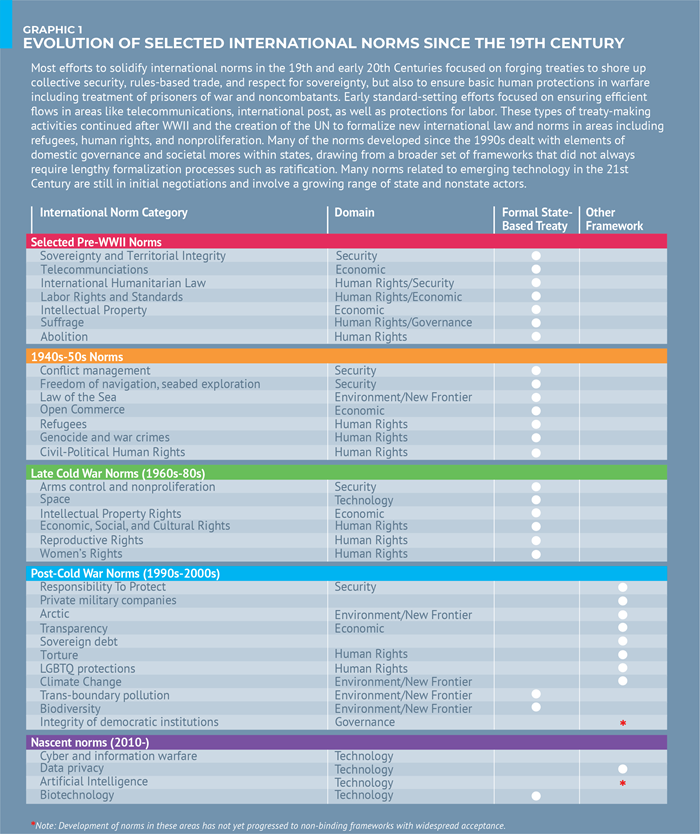

(Graphic 1: Evolution of Selected International Norms Since the 19th Century - Click image to enlarge)

BRIEF HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL NORMS

Norms have been central to the study and conduct of international politics for millennia; Plato and Aristotle considered how morality and justice shaped leaders’ decisionmaking and polities’ behavior, while the Catholic Church devised extensive norms for the conduct of sovereigns throughout Christendom. The norms of state sovereignty and inviolability of borders enshrined in the UN Charter trace their roots back hundreds of years, and the more widely studied international norm-building efforts since the end of WWII built on decades of efforts related to slavery, suffrage, humanitarian protections, copyright, and labor rights. Formal international agreements codified in the 19th and 20th centuries on law of the sea and commerce date back to longstanding European laws and customs. In addition, modern information communications technology and e-commerce relies on technology and commerce standards that emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries related to telegraph, postal, and radio communications.

The adoption and entry into force of the UN Charter following the end of WWII set in motion a dramatic expansion in economic, security, and human rights norm-setting and codification of legal agreements. Western democracies led the establishment of an assortment of international institutions, alliances, and norms of behavior in diverse areas including collective security, individual civil and political rights, rules-based international trade and financial systems, and conduct in increasingly accessible physical domains such as the poles and outer space.

Many security norms were designed to prohibit the most destructive behaviors that contributed to the two world wars. For example, in the 1960s, the nuclear nonproliferation regime was intended to disincentivize any additional states beyond Permanent UN Security Council (UNSC) members from acquiring nuclear weapons, while the norm against acquiring new territories or resources by force sought to contain aggressive territorial expansion.

During the 1990s, a range of states and non-state organizations capitalized on the weakness of proponents of absolute state sovereignty principles, such as post-Soviet Russia, and took additional steps to formalize individual rights norms, which some states interpreted as restrictions on sovereignty. States and transnational networks also banned certain conventional weapons, including land mines, and defined states’ responsibility to protect their citizens and justify external intervention when states failed to protect their citizens and when authorized by the UNSC.

Some scholars suggest that moves to broaden the interpretation and application of certain human rights and humanitarian norms have energized a stronger and more organized backlash, both from governments and domestic groups in democracies. At the same time, authoritarian countries—namely China and Russia—have amassed more power and gained increased confidence to champion alternative norms on the international stage.

AUTHORITARIANS MORE AGGRESIVELY PUSHING THEIR VIEW OF NORMS

Authoritarian governments, particularly China and Russia, are selectively opposing and trying to roll back normative changes made since the 1990s, related to human rights and systems of governance to defend their legitimacy and promote their interests at home and abroad. Their sometimes distinct efforts emphasize non-interference in the internal affairs of countries, based on their definition of national sovereignty. Although they have had mixed success promulgating new agreements in formal multilateral negotiations, over time, the effect of their actions has been to chip away at the political human rights norms championed by democracies in recent decades, such as minority and LGBTQ rights, and provide legitimacy to repressive regimes worldwide.

China, Russia, and many states in the Middle East and Global South are rhetorically advocating strict adherence to the UN Charter’s prohibition on interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign states to enable their actions at home while leaving them room to disregard these restrictions in neighboring states.

- China, Russia, and other authoritarian countries, such as Egypt, have cooperated to frame their domestic crackdowns and military campaigns as valid responses to terrorist threats, including those against Uyghurs, Chechens, or the Muslim Brotherhood.

- China’s foreign and security policy continues to espouse non-intervention; however, Beijing has interfered in other states, notably by retaliating against those that are critical of China or that engage with Taiwan or the Dalai Lama. Western scholars argue that under President Xi Jinping, China has embraced more flexible and limited interpretations of non-intervention, to justify meddling in the internal affairs of neighboring states.

- China is pushing its own definition of democracy and touting its “whole process democracy” as a more representative and effective model than the US system, including by hosting its own international democracy forum and releasing a white paper timed to the US Democracy Summit in December 2021.

China and Russia are also taking more direct and sometimes-coordinated action in international forums to undermine norms related to individual human rights and security, respectively. China is particularly focused on pushing back against efforts to advance individual human rights, whereas Russia is more focused on constraining the use of force by the United States and its allies.

- China and Russia have attacked a range of Western-backed human rights norms at the UN, such as freedom of expression and LGBTQ rights. Russia condemns Western military interventions while defending its own interventions in Georgia, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine. It advocates collectivist economic and cultural rights and prioritizes states’ rights over individual political freedoms.

- In the last five years, China and Russia have had more success weakening the mandates and institutional support for UN human rights country-specific monitoring mechanisms and accountability efforts than they had during the previous decade, judging from UN voting records and academics.

China and Russia are working closely to advance norms on emerging issues, such as cyber, space, and digital information, to promote their broader interests. China and Russia have won UN votes in support of some of their priorities, but their proposed norms most often fail to gain universal backing.

- China and Russia have also used regional and UN forums to coordinate positions and promote alternative cyber and space norms proposals. These proposals seek to constrain freedom of speech online and centralize Internet governance under government control.

- China and Russia insist that national governments have sole responsibility for deciding key policies that affect the information environment in their countries. Since 2018, Russia has used the UN “Open-Ended Working Group” to push its preferred norms on state control over information content as a universal cyber norm.

- Since at least 2016, China has persistently inserted language on state sovereignty and control into negotiations regarding international development finance and Internet governance, while deemphasizing Western-favored norms on responsible lending practices and individual freedoms. China’s surveillance law frameworks and environmental and labor standards have been internalized through formal legislation in many Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries, and BRI investments by China-controlled entities often lack the conditionality of IMF and World Bank projects.

DEMOCRACIES IN A WEAKER POSITION TO DEFEND OR ADVANCE NORMS

Some democratic states that have long championed norms around individual rights and free trade are experiencing more internal debates and in some cases, growing opposition to the free flow of people and information. In recent years, many democracies have struggled with growing societal backlashes to influxes of migrants and refugees, amidst a backdrop of broader economic stagnation and intensified political polarization, much of which has been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- This internal polarization has made it more difficult to forge multilateral political coalitions and for some states to continue to press traditional foreign policy priorities. For example, several European countries have experienced significant swings in foreign policy positions following elections or even government collapse, further complicating the task of building consensus for EU positions. At the same time, ethno-nationalism and identity politics have reshuffled traditional political parties in some countries.

- Democracies with devolved or federalist governing structures, such as Australia, Brazil, India, and South Africa, have further complicated international norms and standard-setting efforts. Cities and other administrative units are championing their own standards and norms on issues ranging from energy efficiency and pollution to LGBTQ rights, often going beyond the national government’s positions and forcing courts to adjudicate.

Domestic clashes within democracies over issues such as pluralism and individual rights continue to seep into international discussions, and some disagreements have intensified because of emergency pandemic measures. Democracies are increasingly split over issues of state authorities and responsibilities, individual rights, and protections for marginalized groups, hampering consensus-building efforts in multilateral venues.

- Human rights: Some democracies have reduced moral and material support for intergovernmental mechanisms such as the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), UN special rapporteurs, and the International Criminal Court. Critics have pointed to the UN’s continued poor record in addressing some of the most egregious human rights violations as well as the growing influence of authoritarian states, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Western NGOs have documented decreased rhetorical commitment for human rights norms during the past several years among many states, including Western democracies.

- Refugees: Many democracies have contravened the 1951 Refugee Convention by severely curtailing asylum rights and deporting refugees to countries where their safety is at risk. In addition, emergency pandemic measures have placed constraints on governments’ willingness to admit refugees.

- Free trade: Certain WTO members have come under criticism from other states and businesses for undermining open commerce and rules-based trade regimes by using national security or COVID-19-related justifications to erect protectionist trade barriers that advantage domestic industries.

While non-democracies and non-state actors have often disagreed with or defied individual rights-based norms, challenges from groups within prominent democratic actors are a newer phenomenon and potentially more destabilizing. Consensus among and to some degree within Western democracies historically has been necessary to broker and institutionalize controversial norms.

- Scholars argue that norms are more likely to decay when the international community fails to condemn violations than when violations are committed. Potential spoilers are encouraged when other norm breakers do not incur punishment or face marginalization.

- Other states, such as Canada, Australia, and Norway, continue to try to defend and advance humanitarian and human rights norms outside the areas of migration, but their efforts have hit opposition in multilateral forums.

EU TRYING TO DEFEND OLD NORMS, ADVANCE PRIVACY NORMS

Some individual EU member states, such as Hungary and Poland, thwarted EU efforts in multilateral bodies to defend human rights; however, the EU as a whole continues to support individual rights and promote new initiatives, such as digital privacy regulations.

- The EU actively champions more contested human rights norms on issues that include LGBTQ and gender equality. However, the EU has faced internal challenges since 2017 to condemning China's human rights practices because of objections from members that have strengthened economic ties with Beijing, such as Greece and Hungary.

- In 2018, the EU started enforcing the Global Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), an effort dating back more than a decade to harmonize European data protection laws. GDPR has placed new obligations on companies, including the right to be forgotten, mandatory data breach notifications, and rules for storage and processing personal data. This regulation is being replicated across dozens of countries outside Europe, and studies have estimated that more than 60 percent of the world's population will fall under GDPR or similar tough data privacy laws in the future.

NONSTATE ACTORS AND SMALLER STATES TRYING TO DRIVE NORM-SETTING

Activists, NGOs, and smaller states are looking for ways to drive norms and fill gaps left by the perceived faltering by some democracies. Nonstate actors continue to contest the efficacy and legitimacy of international norms and institutions, often by building advocacy networks, harnessing technology, and working through state allies in key institutions. Some norms championed by nonstate actors conflict with the stated policy positions of the United States and its allies on topics such as nuclear disarmament, cybersecurity, climate change, and genetically modified organisms.

- Arms Control: Building on past successful examples of pushing through treaties on landmines and cluster munitions, a coalition of NGOs and mostly small states pushed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons through the UN in 2017. The treaty, which entered into force in 2021, prohibits the possession, use, and threat of use of nuclear weapons. Working alongside leading state proponents Austria, Ireland, and Mexico, nonstate advocates used a majority-voting process to negotiate the treaty outside the UN’s main disarmament machinery, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and without support from nuclear weapons states.

- NGOs have played an influential role in UN climate negotiations from the lead-up to the Paris Agreement in 2015 through the UN climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, in late 2021. These organizations have lobbied state parties, advocated for action from sub-national levels of government, reported on negotiations, and monitored implementation. They have also implemented their own carbon reduction initiatives and pressed private companies to reduce emissions. Since 2015, however, many states have not provided details about how they will implement their commitments, and forging consensus on funding and verification has been difficult to achieve at UN climate meetings.

- Activists opposed to genetically modified organism (GMO) food have organized protests across dozens of countries and complicated trade talks among the United States, EU, and other actors for decades.

In addition to civil society NGOs and small states, commercial actors and industry-affiliated NGOs are increasing their participation in international discussions about norms, practices, and standards—looking to protect their assets and goals.

- Given slow movement toward voluntary norms and rules of conduct in cyberspace in formal UN discussions, private-sector actors and states such as France have proposed initiatives aimed at preventing attacks on critical infrastructure, improving cybersecurity, and reducing offensive operations in cyberspace. In 2018, France announced its Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, which condemns malicious cyber activities during peacetime.

- Governments, companies, and civil society organizations have worked together to promote multinational business codes of behavior. They have developed the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, the International Code of Conduct for private security companies, and the Global Network Initiative to encourage companies that have yet to sign onto these standards to adhere to international human rights, as well as environmental, and labor norms and standards. The UN’s endorsement in 2011 of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights marked an important juncture in developing norms around business conduct, and this has been followed by calls for an enforceable treaty.

- Industry-aligned groups, such as Global Climate Coalition and World Business Council on Sustainable development, have joined scientists and civil society organizations to convince states to expand their goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

Nonstate actors, including NGOs, some private companies, and professional organizations, have demonstrated sophistication in setting and implementing norms on issues such as technology and climate change. These actors can leverage existing networks and new digital media to shape public attitudes. They can also encourage private compliance by controlling access to their platforms and wielding their significant financial leverage. However, nonstate actors, with the exception of large multinational corporations, lack the tools to require compliance, and they most often are not monitored or accountable outside their own organizations.

- Business and industry actors have the ability and incentive to influence technology and cyber norms because they produce content as well as software and hardware, own and operate critical Internet infrastructure, and are increasingly liable for cyber attacks against their clients. For example, technology companies can punish transgressions in real-time by enforcing Terms of Service agreements, or by naming and shaming violators.

- Professional codes of ethics have shaped behavior and withstood some normative challenges in emerging areas such as biotechnology. For example, after a scientist in China, Dr. He Jiankui, modified the germ line in a pair of twins in 2018, he was nearly universally shunned by the global scientific community.

DEBATES ABOUT DRONES AND LETHAL AUTONOMOUS WEAPONS PORTEND FUTURE NORMATIVE CONTESTS

Advancements in war-fighting technology present new challenges to norms related to International Humanitarian Law because they can blur the roles of human choice and accountability. Al-powered autonomous weapons, still in early stages of development, have prompted concerns about violations of the laws governing warfare and what constitutes legitimate targeting, particularly because technology cannot be held accountable. Advances in drone technology and concerns about Al-powered autonomous weapons systems have prompted various state and human rights actors to seek to ban or develop standards and norms that would limit their use. These disagreements foreshadow potential fights to come over norms on other types of emerging technologies with security implications.

- Ambivalence among some states and companies about prohibiting research into potentially useful military technology has helped stall progress on developing new norms; China, Israel, Russia, South Korea, and other advanced states are developing autonomous weapons systems.

- The technology's proponents have argued that autonomous weapons may be more humane than human-controlled ones because they can employ the precise minimum amount of force necessary. Opponents have raised ethical concerns about whether autonomous weapons should be empowered with lethal decisions and argue it will not be possible to create an algorithm to anticipate all situations. An international campaign led by human rights NGOs and supported by dozens of states has called for creating an international treaty banning the development and manufacture of lethal autonomous weapons. Google in 2018 published guiding principles eschewing Al for use in weapons systems.

IMPLICATIONS OF A FRAGMENTED NORMATIVE ENVIRONMENT

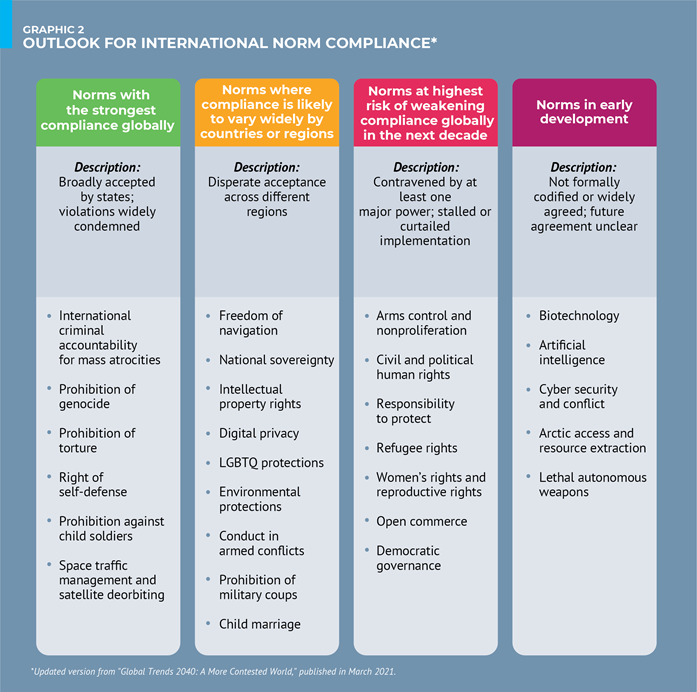

During the coming decade, this diversified and competitive international environment will make it more challenging for many states to maintain commitments to existing norms, establish new norms, solve global challenges, and prevent escalatory behaviors.

- Selective adherence to norms: The broader range of influential actors with divergent interests and goals will further complicate efforts to maintain and monitor commitments to many established international norms. Many contemporary and future challenges will require buy-in from individuals and organizations at all levels. Diminishing consensus among the major state powers is likely to make it more difficult to condemn or punish bad behavior. In this fragmented environment, states and nonstate actors are likely to see fewer risks in ignoring certain norms, leading some to opt out entirely selectively adhere, or offer alternative norms.

- Difficult multilateral norm-setting in traditional venues: Establishing new norms to deal with longstanding or emerging issues will be more complicated and time consuming than it had been in previous eras because of competing normative visions and the lengthy negotiation process. More actors will have opportunities to block progress on rivals’ norms, undercut enforcement for violations, or use sabotage or disinformation campaigns. Treaty- making declined precipitously during the last decade compared with previous decades, judging from international legal periodicals, even as new technological developments and environmental challenges accelerated.

- Fragmenting to localized or regional norms: Some actors will work to shift norms-setting discussions away from the consensus-based intergovernmental institutions to majority-vote formats, or alternatively to regional or nonstate actor-led organizations. In some cases, negotiations on treaties will remain within UN architectures but take place in intergovernmental working groups where a self-selected group of actors controls the agenda. These forums could develop normative frameworks that bear the UN imprimatur while competing with or contradicting existing architectures, potentially undermining the effectiveness of international norms. If norms become more localized for regions or self-defined groups of countries, conducting business and ensuring compliance with future agreements will become even more difficult. Alternatively, norm discussions that begin at the regional level or among affinity groups of actors can serve as the catalyst for broader international negotiations, such as occurred with negotiation processes for the Antarctic and Nuclear Non-Proliferation treaties.

- Less collective action on global challenges: Eroding consensus among certain governments and political factions on the need to respect certain foundational principles will complicate or even stymie international cooperation on global challenges, such as mitigating climate change, dealing with refugees and migrants, minimizing risks from new technologies such as AI and biotechnology, and combating future pandemics. Cooperation in a fractured normative environment is more likely to occur within certain ideologically or regionally defined groups, which could help coalesce action to challenges at lower levels, but will prevent nations from mustering effective responses at the global level.

- Greater risk of confrontation: Declining adherence among some countries to norms on non-violability of borders, assassination, and use of certain weapons systems––in part because of advances in cyber, robotics, AI, and space technology––will increase the risk of miscalculation and conflict. Some of these technologies, if they remain outside normative frameworks, will raise uncertainty among policymakers and make it more likely they will take preemptive action. The availability of these technologies to nonstate actors will also raise the threats to states and risk drawing them into conflicts not of their choosing.

Major powers are still likely to seek to cooperate and uphold norms in mutually beneficial areas, even in an increasingly competitive environment. China and the United States, for example, will still share an interest in preventing further nuclear proliferation in East Asia and the Middle East, containing conflict escalation between nuclear-armed India and Pakistan, preventing global financial crises, containing future infectious disease outbreaks, and avoiding collisions in space. The norms that emerge may be less institutionalized than during the Cold War, but they could still serve as useful checks on risky behavior and help reign-in actions by allies or proxies that threaten to draw the great powers into a broader conflict.

Nonstate actors, along with a handful of key innovative economies, probably will have greater ability to establish norms on emerging technologies than in previous decades, as the pace of innovation and development outstrips most states’ ability to keep pace with new normative and regulatory structures. However, their ability to enforce compliance is likely to remain limited.

(Graphic 2: Outlook for International Norm Compliance - Click image to enlarge)

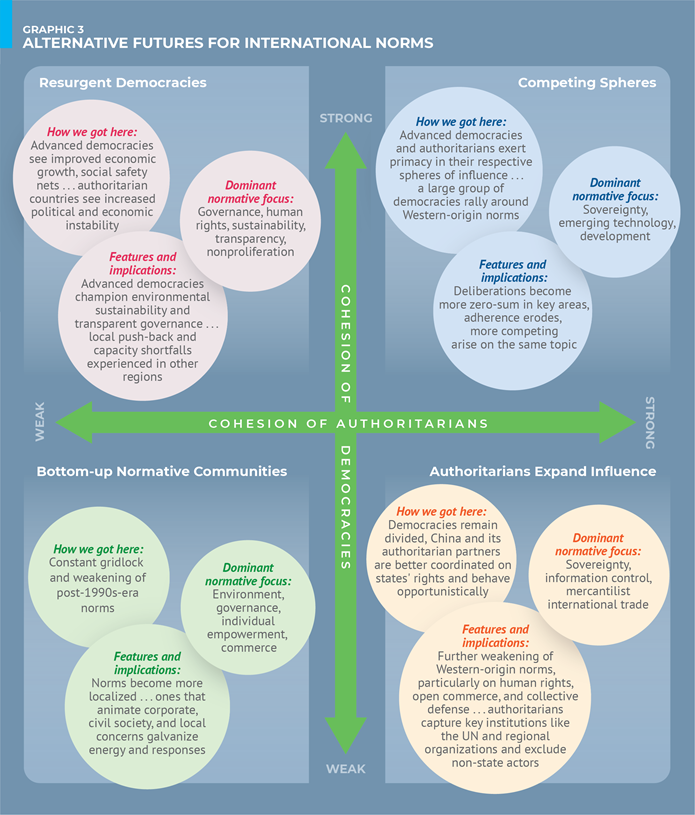

ALTERNATIVE NORMATIVE FUTURES

Over the long term, the future of international norms will depend heavily on the state of geopolitical competition, technological advancements, and societal dynamics. In the following table, we identified four scenarios for how norms could unfold during the next decade, focused on the interactions of democratic and authoritarian powers in the international system. Certain international norms may fall into some or all of these scenarios depending on the norm in question and dynamics among states. For example, human rights and national sovereignty in the information space are more likely to exist in bipolar, competing structures, whereas norms related to the climate and environment are more conducive to bottom-up community approaches.

(Graphic 3: Alternative Futures for International Norms - Click image to enlarge)